Collaboration is completion

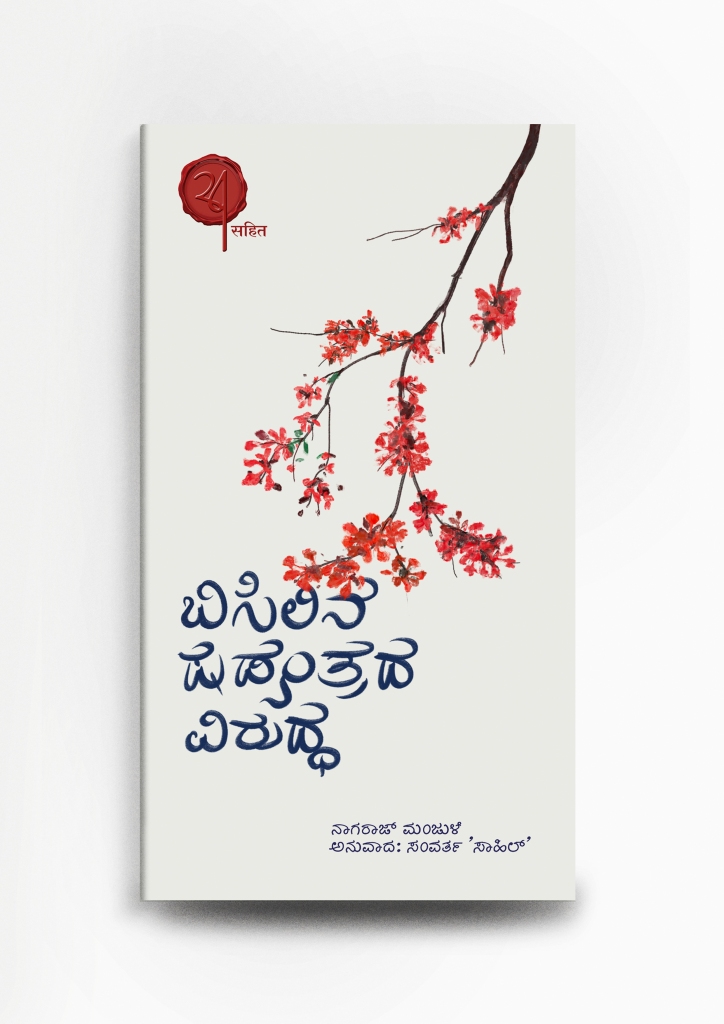

My newly published book- translation of Jacinta Kerketta’s poetry collection into Kannada- has a striking image created by Vandita Jain on its cover page.

Recently when my friend Divya visited us, I gave her a copy of my book. Her daughter Jhari was also present.

The next day Divya recollected what Jhari told her after I left. Jhari picked up the book, looked at the image on the cover, and said to her mother, “I don’t understand Kannada but this book looks interesting.” When asked what about the book did she find interesting, she replied saying, “The leaf is cut and not full”. The mother asked the daughter why she found the half leaf interesting and the ten-year-old Jhari said, “The rest is for us to complete in our minds.”

I think her response tells us something about children– they don’t like to be ‘told’ or ‘shown’ or ‘taught’ but like to be ‘invited’ to the game/ process/ learning.

Jhari’s response also makes me realize why the best of art, and above all poetry appeal to us so deeply. They don’t give us things in complete form. They invite us to join the dots and complete the picture or rather make our own picture. It triggers our imagination!

Probably Jhari’s response also suggests that reality alone doesn’t ‘complete’ things and the real becomes real and complete only with the handshake of imagination.

In addition, her response also reflects the true nature of human life– we have to collaborate towards completion, and that is the joy of life and that is what makes life interesting and fulfilling. Isn’t it? To collaborate towards completion. Or, maybe the completion is in the act of collaboration itself. Collaboration is completion.

Ibrahim, the maverick

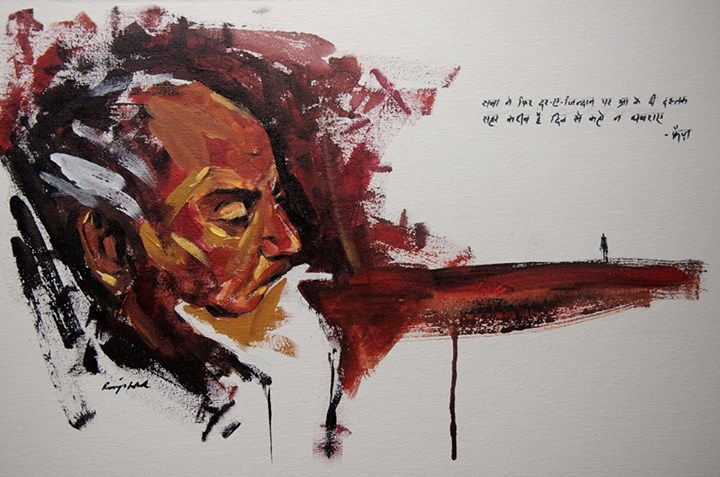

“Hello. Would you have the contact details of Ibrahim Rayintakath?” asked a stranger via DM on Facebook. When I told the stranger I was not in touch with Ibrahim and did not have his contact details, the person said, “I am impressed by his illustration featured as today’s google doodle. So I wanted to contact him”. What?- I exclaimed! I had not seen that day’s google doodle. So Immediately I checked and it was an illustration whose style, though brilliant, did not seem like that of Ibrahim. I checked if it was actually by him and yes, it was by him. A smile appeared on my face- ear to ear! I kept looking at the google doodle for a while and then just lifted my head a bit to look up at a painting hanging on the wall of my room; a painting of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, which Ibrahim had painted for me when we were still students at the film institute (FTII). Looking at both- Faiz and the google doodle of that day- I realized how his style had changed quite significantly, and I was happy that he, unlike many including me, was not stagnating, and was growing as an artist. The smile on my face was still in place and the stretched smile relaxed only when unconsciously a voice from my heart took wings through the lips- Kutty!

Kutty- that is how Ibrahim was referred to and popularly known on campus.

A decade ago… Few months had passed since we entered the campus and our batch of screenwriting was at a crucial junction in developing our first screenplay for submissions. My writing had kept me awake even at an hour when the hostel had gone silent, which wouldn’t happen a couple of hours past midnight. Unable to fight sleep anymore, I decided to shut my laptop and hit the bed. Just when I was about to switch off the light, I saw the water bottle on my table was almost empty. Picking it up from the table, I walked out of the room, to get the bottle filled from the water cooler placed on the floor below ours. As I got down the stairs and reached the floor below, there, next to the lift, stood a lean guy, with sandpaper beard, sketching on the wall. The sketch was a portrait of the maverick filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak! Who is this fellow?- I asked myself in silence, with jaws dropped. Though tempted to ask the man himself, his unwavering focus on his work made it not just difficult but impossible. I stood for a while admiring Ritwik Ghatak being brought to life telling myself, “If God exists and s/he really ‘makes’ us and sends us to earth, maybe this is how s/he worked in the time of Ghatak’s creation”. I filled the water, got back to the same spot, stood for a while more till Ghatak’s painting was completed, and then went back to my room.

Next day I narrated all of this to my roommate Lohit. Incidentally, our friend Maisam, from the Direction dept, was visiting our room then. He said, “That is Kutty. He is from the Art Direction department”. The Direction and Art Direction students had some common classes during the first module and that is how Maisam knew of Kutty, who largely remained silent and recluse from things happening on campus. “Do you know him?” I asked and Maisam answered in the positive. I requested Maisam to take me to Kutty’s room and introduce me to him. Maisam agreed and we went to Kutty’s room. In my mind, I had decided to request Kutty make a painting of Gulzar on the walls of our room. I had shared it with Lohit and taken his consent as well. While discussing this, Maisam had spoken about how Kutty has done paintings of his fav filmmakers on his room wall! When we knocked at the door and Kutty’s roommate opened the door, I could immediately see on the wall a huge painting of my fav filmmaker G. Aravindan! I was floored by how Kutty in his painting of Aravindan had not just done the face of the man but also captured the serenity and calmness of his personality, which was starkly different from the restless personality of Ghatak, which he had captured in his painting of Ghatak too, which I had witnessed just the previous night! Now realizing the extraordinariness of Kutty, I hesitated to ask him if he would do a painting of Gulzar in our room. While I was tossing a coin in my mind, Kutty, who was not visible until then came forward. Maisam introduced me to him. Kutty smiled and said nothing. The smile was welcoming. The coin I had flipped in my mind was still mid-air, Maisam told Kutty why I wanted to meet Kutty. I got a bit uncomfortable and irritatedly turned towards Maisam, almost asking- why did you have to say it? But before I could say anything, I heard someone in the other direction say, “Okay. Will do”. That was Kutty! Now I was smiling ear to ear, which did not end even when the joyful ‘thank you’ came out of my mouth! I immediately asked Kutty, “Please tell me how much you charge for a painting?” Kutty shook his head to say he doesn’t charge. I said, “No, that is not done”, and Kutty interrupted to say, “No, its okay”. It is hard to argue or negotiate with people who are largely silent and keep to themselves. I asked if I could at least get the paints that would be required, and Kutty said no, this time not by shaking his head but by gesturing the same with his hands. We then decided on a day and time for Kutty to come to 404, New Hostel, and do a painting of Gulzar.

Kutty came casually carrying the essentials- pencil, paint, and brush! We moved the bed, cots, and tables in the room and made space for the magic to begin. Kutty stared at the blank wall, made a mental assessment, and took out the image of Gulzar I had given him. Rahul, my classmate, immediately ran to his room and got his camera. “Let me capture the entire process,” he said. Kutty was moving his fingers in the air, staring at the wall from a distance, making an invisible draft of the painting. After a while, Kutty slowly moved closer to the wall. Rahul began to set the focus of his camera. Kutty raised his hand which held a pencil and drew the first line. Click came the sound from where Rahul stood. Magic had begun to unfold.

In the next couple of hours, Kutty brought Gulzar to life in our room. It was like Gulzar had slowly emerged out of the wall. Rahul had captured every stage of the painting on his camera. We proudly said- Now Gulzar is also our roommate! In the end, Kutty posed with the painting for the camera, and Kutty and I together also posed with Gulzar for the camera. These pictures, in a day, went on Facebook. The whole of campus got to know about the painting Kutty did in our room. Some friends visited the room to see the painting and if we ever kept the room door half-open, passersby would peep in and say a word or two admiring the painting. Above all the room’s atmosphere changed with Gulzar coming in, through Kutty. The space which through our living there had already become personal, became even more personal, and our attachment to the room got a bit more intense! Because of Kutty!

Life went on and whenever Kutty and I crossed paths we just exchanged smiles and travelled in our own orbits. But that simple, unpretentious smile of Kutty would recharge my soul. We never met for coffee/ tea. We never sat and discussed cinema or art or even our own lives. But we developed fondness for each other in silence. Some months later, on realizing that I would have to vacate the hostel at the end of the course and with that my relation with the Gulzar painting would come to an end, I requested Kutty to do a painting on canvas which I can carry home with me. He suggested this time we do something other than Gulzar. I had to decide and after much thought, I decided to request Kutty to do a painting of Faiz. I went and bought a good canvas, some paints and brushes in the next few days and informed Kutty about it. One fine afternoon Kutty came to 404 and brought Faiz to life on canvas. Though he had not read Faiz, he almost gave the painting a touch that captured the mood of Faiz’s aesthetics. The strokes of the Faiz painting were different from that of Gulzar, both captured their essence. How did Kutty grasp this? – I still do not know. The magical and mystical nature of creative energy is such, perhaps!

I again took a photo of the painting made by Kutty and posted it on Facebook. Several weeks later one night while sitting and chatting under the Wisdom Tree, fellow student Shwetabh Singh asked, “How do you convince Kutty to do paintings after paintings for you?” and I very casually said, “It requires no convincing. Make a request and he will just do it. He doesn’t throw weight.” Shwetabh expressed disbelief by staring at me with raised eyebrows for a moment. He then told me how some of them had requested Kutty to do a painting for them in their room and Kutty made some excuse! It just made me feel very very special, though I couldn’t understand why he had not agreed to do painting for others. Kutty is a man who follows his heart, his intuition- I realized, and I was glad his intuitive feeling had not come in the way between him and me.

Recollecting all of this, when a stranger on Facebook asked me about Kutty after seeing the google doodle made by him, I wondered where Kutty was! I had not kept in touch with him after I left the campus. We had hardly spoken, so keeping in touch via email or texts made no sense to me, or rather felt very artificial for our silent friendship. But after all those years now I just wanted to know where Kutty is and wished to get in touch with him. I immediately rang Lohit, my former classmate and roommate at the film institute, who had taken admission in the Direction course and was back on campus. He told me how Kutty discontinued his schooling at the film institute after the first year and never got back to complete it! He also told me that Kutty did not keep in touch with anyone from the batch and so nobody knows where he is! I was shocked. But on reflecting the kind of person and artist Kutty as I had seen him, I realized it isn’t surprising that Kutty did not complete the course, discontinued schooling and did not keep in touch with anyone. He was his own master and will always be- I told myself.

That evening Lohit called to tell me Shahi is in touch with Kutty and said he had collected Kutty’s number from Shahi for me. I was overjoyed when he said this and promptly sent me the number soon after disconnecting the call. Once the number landed in my inbox, I wasn’t sure if I should contact Kutty, because we had hardly spoken and also because he had consciously not remained in touch with many from the institute. Contemplating on whether to get in touch with Kutty or not, I took two days to finally drop a text to Kutty. “Hi, this is Samvartha,” I texted. After a few hours, when Kutty saw the text, he immediately replied, “Man! So good to hear from you” and followed it up with, “It has been long,” and then immediately with something that I did not expect coming. He said, “Did you make any films? If you are making films, I will do the posters for all your films.” Kutty had again brought a broad smile on my face and tears into my eyes! “I haven’t done any films yet. I don’t see myself doing one either. But, in case some miracle happens and I end up doing a film, you can do the posters!” The conversation, as expected, did not last long. But it did not feel abrupt, awkward or anything. Even in its brevity it was complete and fulfilling.

For over a year we occasionally texted each other- never asking how the other person is- but sharing some work which we thought/ felt the other person would be interested in engaging with. Then there was a long period of silence. It is during this phase that I had started working on translation of Nagraj Manjule’s poetry collection unhaachya kataaviruddh to Kannada.

After four drafts when I finally met Nagraj Manjule, had an elaborate discussion with him about his poems and my translation, I had decided to rework on the translation one last time and that would be my final draft. Soon after my return from Pune I began reworking on the final draft and also getting ready to go to Trivandrum for the International Film Festival of Kerala, a yearly ritual friend Rachita and I had put into place. Since it was the final draft I was working on and because my translation had been approved by Nagraj, I had started dreaming about the book coming out soon. I had happily communicated to the publisher Kishore that the final version of the translation will be ready soon and suggested he gets ready to publish the book. Kishore was happy and got into the logistics of it. He said, “Once your manuscript is ready we need to do pagination, get an ISBN, and we also need to get the cover page designed”.

After the conversation with Kishore, I was telling Rachita how nice it is to have her by me when these developments are taking place because she was by me when the whole act of translation began. I was also updating her about the journey the translation work has made and how now we are discussing the final stages. Maybe because I was in Kerala or maybe because I was with a friend from the film institute, or maybe because of both combined, or maybe because of destiny, while being preoccupied with the cover design, about which I was discussing with Rachita, I suddenly remembered Kutty! I jumped in the middle of our walk back to the room after dinner, stopped Rachita then and there and asked, “How about asking Kutty to do the cover design?” Of course it had been years and Rachita couldn’t immediately recollect Kutty. “Who Kutty?” she asked. “arrey!” I exclaimed and said, “Ibrahim Kutty, the one who painted Gulzar on the hostel wall”, I said. “Wonderful!” said Rachita in her signature style. Once we got back to the room, I kept typing messages, editing it, rephrasing it etc to send Kutty, to check if he could do the cover design for my book. I was unhappy with every text I had typed, so I decided to give it time and do it the following day.

Next morning while having breakfast, I decided to send a voice note to Kutty instead of a written text. “You once told me you would do the posters for my film. I don’t see myself doing films. But now I have a book ready to be published. Will you do the cover page for it?” I asked in a long voice note where I also explained about the collection unhaachya kaTaaviruddh and the poet Nagraj Manjule. In no time Kutty replied saying he would happily do the cover page. I was overjoyed. Kutty then said to do an appropriate cover design he wanted me to send him the translation of the poems because he did not understand Marathi! Damn! With a sad face I replied to him saying my translation was in Kannada and not in English. “I understand neither of them,” said Kutty and before I could process it, he said, “But I want to do this”. Kutty and I then got on to a call… I was hearing the voice of Kutty after so long! I was happy that he wanted to do the cover page and that I was hearing his voice after so long. In that joyful conversation without me realizing the coffee on the table got cold. But Kutty and I had made a breakthrough. Kutty asked me if I could do an English translation of the poems and also suggested that I could come up with two books simultaneously. I laughed aloud and told Kutty that I am not confident about my English. Kutty asked me to forget about publishing the English translation, but asked if I could do an English translation of these poems just for him to get a sense of the poems. I wasn’t confident even to do that. So I suggested doing a prosaic English translation of the poems and give explanations for the same. Kutty agreed to it. I told Kutty that I would not do a prosaic translation of each poem but only a few, the ones which I think are important and capture the mood of the collection, sufficient enough to hint Kutty on the kind of cover page he could design.

In the next few days I did a prosaic translation of six to seven poems of Nagraj Manjule into English. All for Kutty. On returning home I added Kutty to the chain mail that was being exchanged between Kishore, the publisher, Prajna who was doing the proofreading of all the drafts and me. Introducing Kutty to Kishore and Prajna, I announced that Kutty would be doing the cover-page and also shared with them his earlier works- of Gulzar and Faiz- for them to get an understanding of Kutty and his works. The two of them happily applauded the decision of bringing in Kutty. In a couple of weeks Kutty sent a design for the cover page, an absolutely new style from Kutty! In a few lines he had explained how he did not want to illustrate any poem’s content but wanted to create, through his art, an emotional atmosphere that tunes the readers to the poems. As much as I liked the idea and the thought behind it, I somehow wasn’t convinced entirely by the cover he had prepared. Maybe it was my own bias which was looking for a certain style of Kutty which I associated him with. But Kutty, being the maverik artist that he is, continuously redefining himself and growing in style, had reached newer horizons. Since my relation with Kutty hasnt been either intimate nor just transactional, I could just sit and write a mail to Kutty explaining what about Nagraj’s poems speaks to me, why I find that voice important, why this collection, this translation means so much to me and where I personally stand in my life, what my worldview is and how this project is a reflection of all that. Kutty, the aloof and silent, did not reply to the mail. But in a few days he sent me a rough sketch of the gulmohar flowers, and in a line responded to my mail which showed how he had grasped the essence of my thoughts just perfectly. The cover design by itself spoke for it too! Kutty again made me smile ear to ear… But it was not for too long. Now, Kutty shared his vision of not wanting to use any available font for the cover. “A handwritten text of the title will go well with this,” he said. I agreed with his vision but how were we to make it happen? Kutty doesn’t know Kannada, and I don’t know how to use technology, software etc. Years ago when Kutty had to write a couplet of Faiz on canvas, to accompany the painting, I had written the text in Devnagri script. It was possible also because Kutty and I were in the same physical space and it was manual. Now we were not in the same space and the writing involved technology! There was a knot which had to be disentangled. Kutty then came up with an idea. He said, “Write the text in Kannada and send it to me. I will replicate it here and then you can check if I have got it right.” The idea appealed to me. But now the problem was this- over the years, unused to writing after making a shift to typing, my handwriting had turned worse than what it originally was. So, I made my parents write on a sheet of paper ‘bisilina shaDyantrada viruddha‘- Kannada title of the book, took an image of it and sent it to Kutty. I had used arrow marks to show how the strokes move while writing. Following the cue, Kutty recreated the Kannada alphabets and sketched the title which looked ragefully blossomed- like the central image of the title poem! With that the cover page was almost final. Kutty shared it on the chain mail and Kishore and Prajna also welcomed it.

The time and effort that went into translating unhachya kaTaaviruddh is a story in itself. It took over 6 drafts and the story spans between 2016 and 2022. The process of translation which began in full force in the 2018 monsoon, reached a final stage at the end of 2019 Dec. The plan then was to release the book in 2020 April. When the pandemic hit and the planned release of bisilina shaDyantrada viruddha had to be postponed indefinitely, it ached my heart very much. In those days I have just watched the cover page designed by Kutty and felt better.

In the time between 2020 and 2022 when the release got delayed, I narrated to all my students, batch after batch, the story of translating Nagraj’s poetry collection and also showed them the cover page designed by Kutty. When the world was moving at a different pace and life was flipping between the real and the unreal, and the journey of translation began seeming distant and hence a bit unreal, the cover page made the entire journey seem real. I held on to it.

During this phase, I did get frustrated several times and expressed it before Nagraj Manjule. At times I urged him to agree for an online release event. But Nagraj Manjule convinced me in return to be patient, wait for things to get back to normal. “When you have put so much of effort, why not have the book released in a celebratory manner?” he would ask. Then one day he said, “Even my film has not released because of the pandemic. So I understand your frustration. Let Jhund release first and then after a month of its release, let us release your book”. Those words convinced me entirely.

In Feb 2022 when the release dates of Jhund was announced, I could slowly see my book also coming to life. A conversation with Nagraj enabled us to decide on a tentative date for the release. I immediately dropped a text to Kishore and Kutty to get ready for the final lap of the journey. My enthusiasm was out of control and in consultation with Rajaram Tallur, the preparation began. But there was no response from Kutty. Weeks passed and Kutty hadn’t responded. I sent reminders. No response. Knowing Kutty’s elusive and maverick swabhaava, his sudden disappearance wasn’t surprising. But then, I was getting worried about both- Kutty and the book. So finally I sent a melodramatic text saying it was urgent and Kutty replied saying he has been unwell and has moved to his hometown and his laptop, in which all the works are there, is not with him! My concern about both reached next level. But it is not possbible for me to prioritize anything over human life. Hence, I decided to ask Kutty to not worry and take care of himself. But by then Kutty said its possible that the raw files of the page are on his mail which he can access. He asked for some time to look for it. In a couple of hours the raw files landed in my inbox. On the other hand, by then, the inner pages of the books were designed and ready. Now the cover page was wedded to the inside pages and made ready for print. And in a day, the book was sent to the press.

Few days later Kishore sent some images of the published book. People from the press had clicked photos and sent it to Kishore, which he had forwarded it to me. The quality of the image wasn’t that great and as a result the book cover looked a bit weak. My heart became heavy. But I did not know what to do but hope that the books in real look much different from what it looks in the photograph. That night when Kishore and I spoke, we decided that it would be better if the books are sent to Udupi directly where the book launch event is happening rather than sending them to Bangalore where Kishore lives and then him bringing them to Udupi. Two days later the books were sent to Udupi from Bombay where the book was printed. With my friend Vivek I went to the bus-stop to collect the cartons that carried the books. I was keeping my fingers crossed while driving back home with a carton of books before me, and Vivek sitting behind me on the scooter holding one carton of books.

On reaching home, very anxiously I opened the carton and against all my fears, the book cover had come out extremely beautiful. I held the book in my hand like a young girl holding her birthday gift- a frock that she had desired for long! After checking if the print of the inside pages are fine, and showing my parents the copy, I immediately rang Kutty. It was a video call for I wanted to show him the book. I wasn’t sure if he had recovered, and if he would answer. To my luck Kutty answered and I saw Kutty’s face after almost 9 years! He was smiling, as he always did, ear to ear, and on seeing his face, I too was smiling ear to ear. I showed him the book, with twinkle in my eyes. He got super excited and said, “Oh! Finally!” and I joined him in repeating, “yes, finally!”

Unfortunately Kutty couldn’t attend the book launch event. Few days after the launch, I sent Kutty a copy of the book. When it reached him, Kutty sent an image of it via whatsapp. I could imagine him smiling ear to ear. I texted back asking if he is happy with the outcome. “Definitely am!” he said and added, “Its the first book cover I’ve made.” It was followed with a “Haha” which made me first go “Oh” out of surprise and then laugh with Kutty hahahaha.

I secretly want to believe that many might have approached him for a book cover, but he refused to do it. Maybe some day some Shwetabh will ask me, “How did you convince Kutty to do the cover page?” I wouldn’t have an answer for that. But I would have this long story of my strangely beautiful association with Kutty to share, and a beautiful cover-page to flaunt!

Life Lessons With Deepali

Taking a seat, we recollected how we had first spoken to each other on the way to the very same Cafe almost five years ago. “We had come here on your birthday too,” I said and she nodded saying, “Yes, I remember.”

Deepali and I were meeting after 4 years and the time spent together, four years ago, looked distant and close at the same time. Memories smell fresh when you archive them in your heart with love. They appear so close that the distance traveled in time from those moments surprise you when highlighted.

We had decided the previous night that the following morning we would go to Good Luck Cafe for breakfast, and we did. Taking bites of bun-maska we continued to discuss our common love for old Hindustani film songs and arrived at the song Khaamosh Sa Afsaana from the unreleased film Libaas. I expressed how much I loved the line, “dil ki baat na poocho dil toh aata rahega,” for its simplicity of expression and complexity of experience and also the beautiful way in which that line has been composed and sung. That line took us back to our conversation around how emotions, often opposing, are interwoven and such interweaving holds the truth about us and about the complex nature of life; a conversation which had stemmed out of our session on updating each other about our respective lives in the last four years.

The whole of that day we kept singing that one particular line and kept wondering whether the line expressed fear, relief, hope, or disgust. We were also struck by how the line begins with a denial to engage with the question (na poocho) and ends with a kind of understanding/ surety (aata rahega) of things unfolding/ happening the way they ought to happen. That “aata rahega” also voices, we recognized, is a kind of giving in to life and a willingness to go with the flow. This denial to engage and the willingness to go with the flow with the understanding/ surety that things will happen the way it has to, we came to believe, is beautiful not because the truth lies between them but because the truth lies in their coexistence.

The previous evening, when Deepali and I sat at a restaurant with our friend Dharma, she had explained the tattoo on her hand, something which wasn’t written on her skin when we were studying together at FTII. This new tattoo which looks like her obsession with music, she explained to us, is actually more than just a reference to the icons on the music player. She said, “the rewind button stands for a past that exists, the forward button reminds of the future that is to come. The pause icon is a reminder of life/ relationships/ associations not stopping ever but only pausing temporarily. In my life there is no Stop button. There is also an icon of mix which indicates that life doesnt flow in chronological order. all these icons are there in black, which means they are not in motion though they all exist. The only icon in motion, hence in red, is the play button icon. life is moving on and I am moving on with life.”

While returning to the campus from Good Luck, Deepali said she would like to record the song and it was decided that at night we would record the song in her voice. Making this decision Deepali started rehearsing the song in a very non-rehearsal kind of way, while we continued with our conversations, cooking, eating, and walking. As she kept rehearsing, I kept wondering at the similar undercurrent between what we conversed the previous evening and our conversation on the following day- about life, about humans, about relationships.

Life unfolds in its own way and probably the only way to be in tune with life is to go with the flow, dance to its rhythm, and breathe its air.

Every time she rehearsed, the line sounded different and I remembered what Sheila Dhar in an essay had mentioned about recording music/ singing. Sheila Dhar, I recollect from my memory of reading the essay, says that recording is only a reference to the raga and not the raaga itself. She says every raaga is like an incense stick and every rendition like the smoke that the incense stick exhales. The pattern, the formation, the movement differ every time though it is the same raaga. Similarly, though the same song it was different each time Deepali rehearsed it and sung it.

No amount of preparation can guarantee you that a song will be sung the same way as imagined in the mind. Probably it is the song which guides us each time and each time, we follow it differently. Maybe that is true of life too.

The Untranslatable Poetry

In the year 2017 when the publishers of my first book sent me the complimentary copies of my book, I showed it to my mother with great pride. My mother smiled reading its title ‘rooparoopagaLanu daaTi‘ and asked me what was the book about. I told her it’s a compilation if 74 poems from across the globe, from different languages, translated into Kannada by me. She said nothing after that went back to cooking, and I got back to my room.

In some time Amma knocked at my door and when I opened she held a bowl of gaajar ka halwa… She scooped out a spoonful of halwa, put it in my mouth saying, “I dont understand poetry, but I am very happy for you.” There was mist in her eyes.

As I got back to work station, with halwa in my mouth and tears in my eyes, I realized that the best poetry is mother’s love. That, I realized, I will never be able to translate.

***

That evening when I natrated this to my friend Randheer Kaur, she recollected a poem by Surjit Patar, originally written in Punjabi, and roughly translated it for me into English…

The poem by Surjit Patar in the translation of Gurshminder Jagpal reads:

My mother could not comprehend my poem

though it was written in my mother tongue

She only understood

son’s soul suffers some sorrow

But with me alive

wherefrom did his sorrow arrive

With utmost keenness

my unlettered mother gazed at my poem

Look!

The womb-born

conceal from mother

and confide sorrow in papers

My mother picked the paper

and held it close to bosom

Perhaps, thus

would get closer

born from me.

(Originally written as an Instagram post on 2021 mothers’ day)

Relationship with Languages

Someone with whom I shared an intimate bonding, once told me, “I can have sex only in English.”

Their words made me reflect and I realized I feel hungry in Kannada, think in English, experience pain and love in Hindustani, and my struggle with mental-health is in all three languages.

Some people like me are torn between languages.

Kannada has given me the earth to be rooted in, English has granted me the sky to fly and Hindustani has tempered my heart to feel a connection with things. But the language of my inscape always is: silence.

I have a complicated relationship with languages.

(Note written on the occasion of International Mother Language Day observed on 21 Feb)

“Poetry for him is an Ordinary Mystery.” : Guillermo Rodriguez on A.K. Ramanjuan (Interview)

Samvartha ‘Sahil’: My first question or rather a request to you is to define the corpus of AK Ramanjuan (AKR) through an image or a metaphor and explain the different dimensions of AKR that get reflected in that image/ metaphor.

Guillermo Rodriguez: There are a series of crucial metaphors in AKR´s life and poetry, and many of them are related to nature, such as the (upside down) tree, the orange (fruit) in the tree, the snake etc. But I would say that (window-)glass is perhaps one of the most enigmatic and powerful images in AKR`s poetry as well as in his aesthetics. He once scribbled in his diary notes, “glass is good, it reflects to the outsider and refracts for insiders”.

That is, depending on the point of view (where you stand) and how light hits the glass, you may either see yourself in a mirror reflection or see through the window to the external world, to the outsider who in turn may not see you standing behind the glass but see his own reflection. The window-glass is therefore a metaphor of the complexity of the human “self” which is invested with an inner and outer “vision” and composite “relations”. And glass is fragile, as is “the self”; it can break into pieces. Ramanujan´s choice of glass metaphors also testifies to his kaleidoscopic view of the world and to his belief that “truth is only in fragments.” In his poetry there are abundant glass and mirror metaphors. He often plays with perception, view points and optical effects, showing us how an image can be constructed from a concrete visual sense impression and then move beyond the particular in concentric circles, expanding meanings and reflections; thus performing a poetic play of mirrors, as it where. The related concepts of reflexivity and self-reflexivity were also a central to his understanding of Indian literature.

SS: Can you map the ‘becoming’ of AK Ramanjuan, tracing his journey as a writer and thinker? It would be great if you can mark the major milestones and turns/ shifts of this ‘becoming’. I mean evolution of his intellectual and creative self.

GR: There were several crucial moments and milestones in AKR`s life which defined his intellectual evolution and writing career. In 1943, for instance, when he was barely fourteen years old, AKR failed a final exam in history, which made him turn to writing prose and poetry in Kannada. Another decisive moment in his youth was when he threw away his sacred thread, thereby shunning his Brahmin tradition and legacy; instead, he embraced rationalism, existentialism and other philosophies, as well as medieval Kannada Virasaiva bhakti poetry which advocated an anti-brahminical revolutionary stance. Years later as a Professor of English in Belgaum in the early 1950s he was drawn to folklore and collected oral tales and women narratives. This was also a very fruitful period in his life as he began to flourish as a poet in English. In 1958, tired and disappointed with teaching English, he decided to study linguistics in Pune which eventually took him to the USA in 1959 as a Fulbright Scholar. His moving to America, and his constant “in-betweenness,” crisscrossing between disciplines, traditions, cultures, and tensions, moulded his multicultural intellectual profile and fed into his creativity. Linguistics and structuralism as a young researcher and professor in the U.S. in effect became the foundational ground on which his intellectual “toolbox” rested. This, along with his accidental discovery of an anthology of Tamil classical Sangam poetry in the basement of a library at the University of Chicago, marked his scholarship as well as poetic style which stayed with him throughout his career. In the latter phase of his life his structuralist convictions were shaken by post-structuralist theories (the later Barthes, Kristeva, Derrida etc.) which he also absorbed creatively into his own thinking and work as a writer.

SS: Like the title of his essay 300 Ramayanas we can say that there exist 300 Ramanujans, though 300 might sound a bit of an exaggeration. But the Ramanujan as a poet, as a translator from English, as a translator to English, as an essayist, as an anthropologist, as a writer in Kannada, as a writer in English, as a reader in Kannada, reader in English, reader in Tamil, as a researcher. How do these various facets of AKR flow into one another and influence one another? As an interviewer, on behalf of the (imagined) readers I request you to elaborate on this with some examples.

GR: AKR`s life and work was multi-layered. Moving from his native Mysore to Chicago and around the world, wherever he went and worked he continued to enlarge his multidisciplinary outlook both as a scholar and artist. This heterogeneity was further nurtured in his manifold professional engagements at the University of Chicago. He stated in an interview conducted by Chidananda Das Gupta in 1983: “One of the fortunate things of my life is that I have been able to keep the miscellaneousness interests of my youth alive – because I landed up in a place where this was formally recognised. It’s good to feel that these interests are not hobbies I pursue outside my field.” In AKR’s intellectual and artistic “miscellaneousness” there is, however, a continuous dialogue and reflexivity, which were also characteristic principles of Indian literary texts as he stressed in his essays. The multiple traditions, languages (mainly English, Kannada, and Tamil) and disciplines AKR absorbed therefore formed a very creative interaction in his self and in his work encompassing the diverse scholarly interests, the poetry, as well as the translations. In his work as a scholar and translator he imbibed terminology from linguistics, literary theory, classical Tamil and medieval bhakti aesthetics, cultural anthropology and other disciplines which he constantly revised. And his interests remained always in balance between the “higher” arts and disciplines and the popular forms of expression such as traditional oral tales or proverbs. These multiple realities were not independent variables but inter-dependent branches of the self.

SS: Is there a Ramanjuan way of crafting words, inclusive of his pre-verbal thoughts, and what defines it?

GR: The process of writing for AKR is cyclical and open-ended. There is no conclusion in poetry; poems for him, as Valery said, are “only abandoned.” He did not believe in a pre-verbal, original form before it comes to the poet, that is, in the existence of the poem before it is written. As a trained linguist he was very conscious of language and for him only through the process of writing and re-writing and revising did the poem come into being, as “a form emerging like a face in the water.” As he explained, poems often started as a ”stir”, but then they needed to be carefully nurtured and cleaned up until they matured, lest they got “lost” or spoiled. This we learn, for instance, in the poem “Children, Dreams, Theorems.”

SS: Can you elaborate a bit on AKR’s fear, while writing, of not being able to write poetry again? And please throw light on what does this fear speak at large about the writer AKR.

GR: One could say that AKR’s suffered from an acute existential anxiety, and this became almost a chronic state. He was constantly “looking for the centre” and to deal with his recurrent fears and personal depressions he often sought advice in psychology. But writing poetry also became a way of finding himself; poetry could simultaneously be the cure and the site where his existential tensions were creatively expressed. Even a good number of his early poems from The Striders (1966) deal with the anxiety with which all poets look for inspiration and tackle his worst nightmare: the fear of the self-conscious poet whose mind is full of images, phrases and words of other poets, but who is not able to make them his own. This fear, along with his primordial fears (various types of animals, but also sex, death, drowning or falling etc.) haunted AKR throughout his life.

SS: AKR seems to have been fascinated by what we can call ‘ordinary mystery’. Do you see this as an undercurrent across his body of works? How does he arrive at these ‘ordinary mystery’, articulate them and decipher them in his works?

GR: I deal with this interesting issue at length in my book When Mirrors Are Windows. AKR’s poetics is aware of the metaphysical dimension of artistic grace, yet in his poetry he wanted to show how poetry is different from divine inspiration in that it “works” somehow like ordinary life. He developed a pragmatic attitude to art and life. And so his concept of grace does not recognise a superior force; AKR sees art as a special type of event that can happen anytime, it may come as natural “as leaves to a tree, or not at all” (a quote he borrowed from Keats). Poetic inspiration is therefore expressed as a paradox, for him it is an ordinary mystery: “Poetry happens unbidden and has to protect itself,” he said in 1980 in an interview by Murali Venkatesh, “it’s a mystery, but mystery itself is ordinary. Only we make of it something miraculous.”

Even if the right images and words come to the poet, the origin of imagination still remains a mystery to him. So many of the poems, and in particular, the ones he wrote during the last phase of his life and which are collected in “The Black Hen” (published posthumously in 1995), deal with this “mystery” and play with the notion of poetry writing. One only has to read between the lines to see that there is as meta-poetic undercurrent in much of AKR`s oeuvre that attempts to illustrate or perform the “ordinary mystery”.

(Interview conducted via email in March 2018 for Ruthumaana and published on AKR’s birth anniversary – 16 March- in the year 2020)

Gulzar 85

Yesterday, the 18th of August 2019, Gulzar sahab turned 85.

In the year 2012, Nasreen Munni Kabir came up with her book of conversation with Gulzar titled ‘In the Company of A Poet’. Eagerly waiting for the book I had pre-ordered a copy for myself. When my copy of the book arrived, I was on my way out of the hostel for late breakfast at a nearby shack. Excitedly I collected the book from the courier boy at the gate of the hostel, tore open the cover hurriedly and began reading the book as I marched towards the shack. As I kept reading and walking on the footpath, I rammed against the electric pole. My leg got injured. It wasn’t a major wound but still a wound. I limped to the shack continuing to read as I limped.

I might sound silly or even stupid, but I wanted to preserve that wound. I dint want it to heal because to me it was a sign of the maddening love I feel for Gulzar sahab. I wanted that wound to be over my body, like a badge of love. I was sad as the wound healed and it was the only time I mourned the healing of a wound.

There are plenty of other invisible wounds deep within me, that refuse to heal. Those wounds are occasionally consoled and comforted by the poems and songs penned by Gulzar sahab.

Thanks Gulzar sahab.

Songs For Dark Times

Bertolt Brecht, the German dramatist and poet, in a poem asks if there will be songs in the dark times, and answers the question as, “Yes there will be songs about the dark times.” Nada Maninalkur who now is on an all-Karnataka journey asks and also answers the possibility of turning songs into light, not just to walk cutting through the dark times but also to fight the darkness.

***

As Nada Maninalkur sings the song by Janardhan Kesaratti which asks the listener to cleanse the dirt accumulated in the mind (manssiganTida koLeya tikki toLeduko) he pauses to ask, “How many of you feel healthy?” and the high-school students raise their hands. “Do you notice that all of you have raised your right hand?” asks Nada and the students wonder what is so unusual about it. When Nada follows it with, “Why do you raise your right hand always when you have to ask a question in the class or know the answer to a question asked by the teacher?” the students are pushed to think why for the first time. Nada helps them to find the answer when he says, “We have all been schooled to think that right hand is superior to the left, like white is superior to black. This hierarchy and discrimination is taught in the form of culture.” The students are visibly unsettled by the new thoughts but also have started finding such hierarchy wrong.

As Nada Maninalkur sings the song by Janardhan Kesaratti which asks the listener to cleanse the dirt accumulated in the mind (manssiganTida koLeya tikki toLeduko) he pauses to ask, “How many of you feel healthy?” and the high-school students raise their hands. “Do you notice that all of you have raised your right hand?” asks Nada and the students wonder what is so unusual about it. When Nada follows it with, “Why do you raise your right hand always when you have to ask a question in the class or know the answer to a question asked by the teacher?” the students are pushed to think why for the first time. Nada helps them to find the answer when he says, “We have all been schooled to think that right hand is superior to the left, like white is superior to black. This hierarchy and discrimination is taught in the form of culture.” The students are visibly unsettled by the new thoughts but also have started finding such hierarchy wrong.

Nada Maninalkur has been travelling across all the districts of Karnataka since August, 2018 with around 50 songs which speak of various issues like gender, caste, superstition, social inclusion, pluralism etc. When Nada announced his ‘Karnataka Yatra’ on social media, individuals, organizations, educational institutions from all districts invited him to come perform for them and promised audience too.

In a B.Ed college, a set of students who earlier walked out of the concert by Nada come sit by him while having lunch post-concert. They say, “We disagree,” in a self-guarding tone. Nada smiles and continues to eat. Later when he is about to leave the campus the same students come to him again and say, “We have been thinking about it. But still we disagree.” Nada says, “I am glad you are thinking,” and continues to say, “My job is done.”

The back story of this story goes like this:

At this particular B.Ed. College, Nada decided to begin the concert by singing kalisu guruve kalisu, a song which originally is a letter that Abraham Lincoln wrote to his son’s teacher. Like the method he employed for this journey, this song rendition too was paused for conversations after every stanza. At one point the conversation moved to the popular Kannada folk song govina haaDu (song of the cow) which tells the tale of a tiger killing itself after witnessing the truthfulness of a cow named Punyakoti who it wanted to eat earlier. Nada Maninalkur, referring to this song, spoke about poetic imagination and its politics which made some among the audience uneasy and restless. Next when Nada sang the song, namma elubina handaradallondu, (There are places of worship- temple masjid church- and Gods in our skeleton) a bunch of students got up to say, “This song is unscientific. How can there be a temple or a masjid inside us?” Not satisfied by the question they raised, the statement they made the students also walked out of the concert. Later at the mess he met the same set of students who came to him to register their disagreement yet again.

Recollecting these episodes Nada Maninalkur says, “Change is a process. When the first stone is thrown it stirs the water and muddies the water. But slowly it also creates ripples.” He continues the conversation to say, “Songs by themselves are inadequate. But they can initiate a dialogue in a much effective manner than a lecture or a sermon. Hence I use songs while the most important thing for me is to have a dialogue with people.”

Nada Maninalkur who started Arivu, an NGO, in 2012 arrived at this understanding slowly through personal experiences. The one major incident that made this realization dawn on Nada was a series of programmes they held after an infamous rape incident of a young girl in the Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka. The Arivu team visited college after college and discussed body politics using theatre, songs and literature. That made students open up, though it made the lecturers uncomfortable. “Education is left with no space to think alternatively and think rightly. This space needs to be filled and songs can become an effective and immediate way to build bonds and initiate a dialogue,” says Nada and recollects another story from the same time period.

A lady teacher who came from a conservative family came in contact with Nada and team while they were working with some of her students. Over a period of two years the teacher who earlier would insist on purity of food, water and not share her food or water with anyone, eventually cast off her casteist worldview and now holds a liberal outlook. This was possible, according to Nada, only because of a continuous interaction with humanistic ideas and continuous dialogues with fellow humans, outside the boundary of caste class and gender. Now the same teacher helps over 200 students a year to shed off their biases and reinvent their ‘self’, says Nada.

In Nada’s opinion, “In our growing up years we spend most of our time in educational spaces and hence it is important to speak in educational spaces.”

“Working with ‘Self’ is important,” opines Nada and elaborates on it. During this ‘Karnataka Yatra’ at a school in the district of Shimogga when Nada sang a song on menstruation, the dialogue with students arrived at the issue of Shabarimala. During this discussion a student said, “Respecting belief and practice is a part of our democratic values.” Nada spoke the importance of respecting people’s faith and practice and went to speak about the beliefs and practices which harms human, like caste etc and also narrated the story of Nangeli. The student then agreed with Nada when he said, “We need to get rid of beliefs and practices when they do not respect human dignity and doesn’t believe in equality.”

In other schools, Nada remembers, whenever he sang the song on menstruation, the students would either giggle or put their heads down in embarrassment. In a school, he recollects, a girl who spoke about menstruation covered her face with a scarf while speaking. The girl said that this issue is not discussed in a normal way even among girls. “We are made to believe that it is a shameful thing,” Nada says and adds in a firm voice, “We haven’t worked on ‘self’ and hence we fail to build on the idea of rights and justice. First we need to realize and make people realize that the dignity of ‘self’ is of utmost importance.”

In other schools, Nada remembers, whenever he sang the song on menstruation, the students would either giggle or put their heads down in embarrassment. In a school, he recollects, a girl who spoke about menstruation covered her face with a scarf while speaking. The girl said that this issue is not discussed in a normal way even among girls. “We are made to believe that it is a shameful thing,” Nada says and adds in a firm voice, “We haven’t worked on ‘self’ and hence we fail to build on the idea of rights and justice. First we need to realize and make people realize that the dignity of ‘self’ is of utmost importance.”

Though most of the concerts of Karnataka Yatra have been in schools and colleges, Nada as a part of this Yatra has also performed in Temples, Masjids, Central Jail. He has also accepted invitations of activists, youth groups, journalist circles etc. In all these places, he says, he would first asses the audience and on the spot makes a choice of the songs to be sung for them. He has been singing 4-5 songs in each concert from his archive of around 50. Most of these songs are from contemporary Kannada poets. But his archive also includes verses by the 12th century Vachana movement and of saints like Shishunala Shareef, Kabeer etc.

Even when Nada is in the last leg of his Yatra, to his credit, not even once he has been stopped from singing or discussing in any of the districts of Karnataka. But yes there have been discussions of high voltage, which is okay according to him since there is still dialogue happening there. This, he says, is the power of songs. It makes you introspect, he opines, and it doesn’t have the aggression which one way communications such as lectures and seminars carry. Songs make space for a dialogue, for conversations to take place, opines Nada. The proof, he says, is seen in the invitations he got from teachers in several schools to teach the same songs to the students and also the invitation he received from some teachers to come stay with them for that day. The students, he says, either openly come and talk to him or write letters to him or tag him on social media and thus express their acceptance of and appreciation for the pedagogy he employed.

Nada also has some funny anecdotes to share like instances where people considered him to be a religious saint and would come and offer dakshinNe (money offered in kindness) and a particular instance where someone equated him with an extreme right wing speaker saying, “You too travel to inspire the youth, like him.” Nada’s reply to this person was simply, “I am not here to inspire youth but to sensitize the youth. That is the difference. Also, he speaks politics and I speak about humans and human self.”

A friend of Nada suggested him to bring out a CD of these 50 songs with which he travelled across Karnataka and Nada politely rejected the idea. His reason for it is spelled out like this: “If brought out as a CD, these songs will turn into a commodity of entertainment and it will just become one with the innumerable songs of this world which some sing and some remember. To me the dialogue that these songs initiate is important.” That is precisely why Nada says that when he was asked to teach these songs, he suggested a one month residential workshop, “because it is not just about learning the lyrics of the song in a particular tune and singing it in a melodious manner. It is not about songs but responding to the times and holding a dialogue. For that one needs to be trained in things other than music.” Nada himself isn’t a trained singer nor is he trained to play the two stringed instrument he plays.

“When I started this journey, I started with great despair. But this travel has made me hopeful. I have learnt during this journey that there are innumerable human beings out there in the world who are doing several work in small scale which is making a positive impact on some life. There are unimaginable number of people who in their daily lives are keeping the spirit of humanity alive. This they are doing not because they think it is their duty but because it is their default nature,” says Nada before he continues with his journey with songs in his pocket.

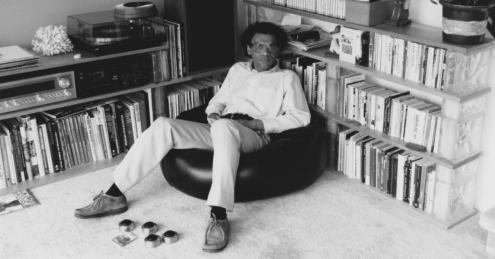

Happy Birthday Ghalib

Today happens to be the birth anniversary of the unparalleled Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib. There is a lot that has been written about the master poet and his poems have been understood, explained, analyzed and interpreted multiple times. It would sound a cliche if I am to say Ghalib’s poetry offers something new every time one revisits them. But I have known it from my own experience that, with more life experience one experiences Ghalib quite differently and more deeply. With age Ghalib only becomes more and more apna!

I am not someone who longs for a long life and sometimes fear having a long life. In such moments I tell myself, “Imagine what more meanings and truths of life will flow out of Ghalib at that age!” And that excites me. I wonder what hidden gems will emerge from within his poetry when engagement with life gets more intensified. A long life will be worth it just to look at oneself and one’s life in the mirror of Ghalib’s poetry, in the light of Ghalib’s poetry.

This photo is from the restaurant section in a hotel in Haygam, Kashmir named Time Pass. I was put up in this hotel during my visit to the valley this summer and on seeing Ghalib’s portrait there I immediately felt at home though it was my first time there.

Happy birthday Ghalib and thanks for everything.

Raag and the Rain

One afternoon, in the third week of this April, I was with my friend Randheer in Jammu University. I had gone back to that campus after two years. In a while, our other friends- Sonia, Nisha and Shaabaaz joined. As we sat under a tree with chai in our hands, we requested Nisha to sing and Shaabaaz to recite his poems. Understanding the mood of the situation, Shaabaaz called his friend Aakash, a trained and passionate singer, to join us. Akash was with us in two minutes.

Nisha began the mehfil by singing a gazal by Begum Akthar. After Nisha sang and Shaabaaz recited his poems, now it was Akash’s turn. Akash sang quite a few songs and ghazals for us, pausing his singing to explain which raag it is, other musical details and some related anecdotes. Once while he was explaining a raag to us, the impulsive and innocent Sonia asked Akash if its true that some raag bring rains and some light the lamps. My immediate reaction was, “What a juvenile question,” which of course I did not say loud. I do not know what others thought but Akash clearly did not think so. Very spontaneously he said, “I am not sure if it happens in the outside world. But it has happened within me. I have witnessed rain within me, while listening to some raag and have witnessed lamps being lit within me, while listening to some other raag. That is all I can say.”

I was glad Sonia asked that question. When Akash’s singing continued, I could feel a new vibration within me.